‘Worst Disease Possible’ Explained After Mom-of-Two Ends Life by Starving Herself to ‘Protect Her Children’

© stupid_mnd / Instagram

A devastating disease stole a mother’s ability to hold her children, speak clearly, or breathe with ease.

Her courageous story has ignited discussions about the right to decide one’s own end-of-life path.

This article delves into her choice, the struggles of terminal illness, and the wider battle for control over death.

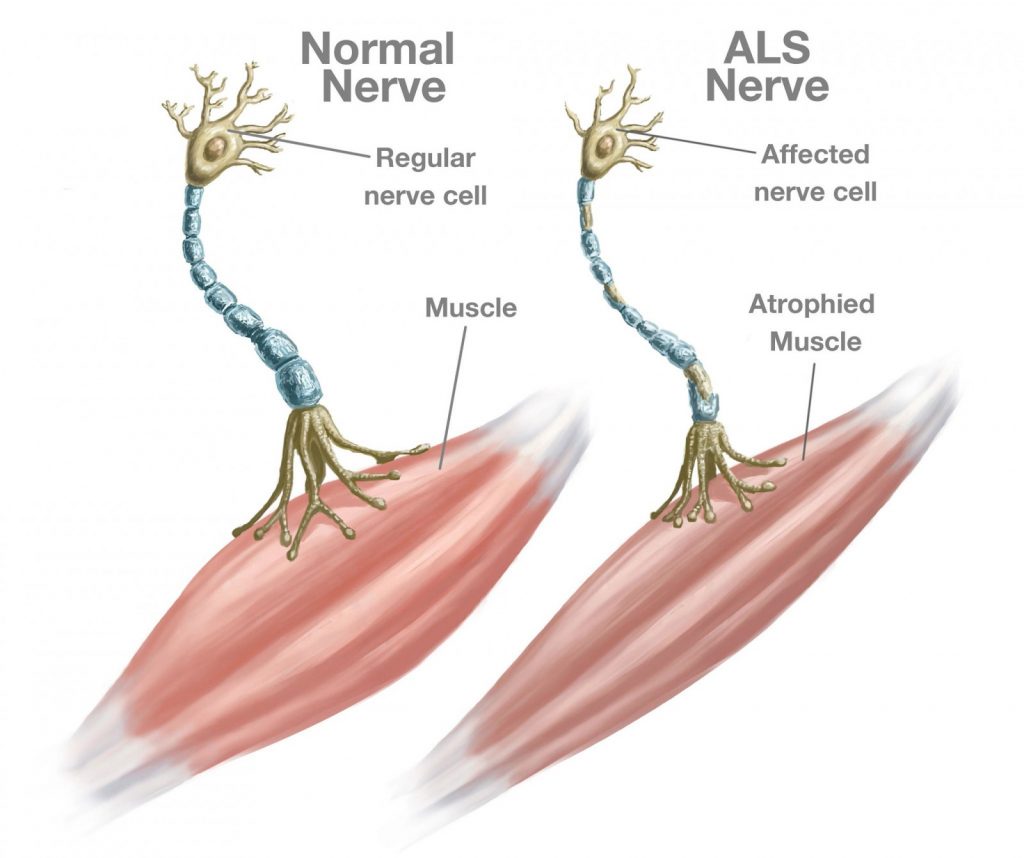

What is Motor Neuron Disease?

Motor Neuron Disease is a group of neurological disorders that damage motor neurons, the nerve cells in the brain and spinal cord that tell muscles what to do. When these neurons stop working, muscles weaken, waste away, and can no longer move properly. This can affect actions like walking, talking, swallowing, or breathing.

MND includes several types, with ALS being the most common, affecting both upper motor neurons (in the brain) and lower motor neurons (in the spinal cord). Other types, like Progressive Bulbar Palsy (PBP), mainly impact speech and swallowing, while Primary Lateral Sclerosis (PLS) affects only upper motor neurons and progresses more slowly.

Symptoms often start mildly, such as stumbling, slurred speech, or muscle twitches, and worsen over months or years. According to the NHS, MND typically affects people over 50, but it can occur at any age, with men slightly more at risk than women.

What Causes MND and Who’s at Risk?

The exact cause of MND is still unclear, but researchers believe it’s a mix of genetic and environmental factors. About 10% of cases are hereditary, linked to gene mutations like SOD1 or C9orf72, meaning they run in families. If a parent has MND, the risk for their child is slightly higher—about 1.4% compared to 0.3% for the general population.

Most cases (90%) are sporadic, with no family history, possibly triggered by factors like exposure to toxins, viral infections, or head trauma, though evidence is not conclusive. For example, a 2012 study suggested footballers may have a higher risk of ALS due to repeated head injuries.

MND is rare, with a lifetime risk of about 1 in 300 by age 85, and around 2,752 Australians are living with it at any time. It affects people worldwide, regardless of race or lifestyle, but is more common after age 40, peaking between 50 and 70.

A Devastating Diagnosis

Two years ago, a 42-year-old mother from Barnstaple, England, named Emma Bray, received a diagnosis that changed everything: motor neuron disease (MND), often called ALS or Lou Gehrig’s disease. This condition attacks the nerves that control movement, leaving a person unable to walk, talk, or eventually breathe.

Emma described it as “the worst disease possible” after four health professionals confirmed its severity. As her condition worsened, she could no longer use her limbs, struggled to eat, and found social visits exhausting.

The thought of her teenage children, aged 14 and 15, watching her decline was unbearable. “I can’t hug them or wipe their tears away,” she shared, highlighting the emotional toll of MND.

Choosing Her Own Path

With assisted dying illegal in the UK, Emma made a difficult choice: voluntarily stopping eating and drinking (VSED). This method, where a person refuses all food and fluids to hasten death, is legal but grueling.

Emma chose this path to spare her children from seeing her suffer through the final stages of MND, which can lead to choking and breathing struggles. On July 14, 2025, she shared her decision on Instagram, posting a final photo from her hospice bed.

“VSED is not an easy death,” she explained, “but it’s the only way I can have control over my death.” Her choice has reignited debates about whether people with terminal illnesses should have legal options for a dignified end.

The Fight for Right-to-Die Laws

Emma was part of Dignity in Dying, a UK group pushing for assisted dying to be legalized for terminally ill, mentally competent adults. Her story echoes others, like Jean Davies, who, in 2014, starved herself for five weeks to end her life, calling it “intolerable” due to the lack of legal alternatives.

In the US, some states allow assisted dying for those with life-threatening conditions, but in the UK, it remains illegal, forcing people like Emma to turn to VSED. Supporters argue that legalizing assisted dying could provide a less painful option, while critics worry it might pressure vulnerable people into ending their lives.

The debate continues, with a UK bill proposed in 2025 to allow life-ending medication under strict conditions, showing how Emma’s story is part of a larger movement for change.

Her decision wasn’t just about her own suffering—it was about protecting her children from trauma. As conversations grow, her story challenges us to think about what it means to have control over our final days and how society can support those facing the hardest choices.

You might also want to read: Right-to-Die Activist Ends Life by Starving to Prevent Children From Seeing Her Gasp for Air